“There is no such thing as a quantum leap. There is only dogged persistence – and in the end, you make it look like a quantum leap.” James Dyson

Hey Coaches,

Here you go!

✍️ Articles

Berkshire Hathaway 2025 Annual Letter

Here are a few takeaways from Warren Buffett’s annual letter, which was published last week:

On Personnel Decisions - “A decent batting average in personnel decisions is all that can be hoped for. The cardinal sin is delaying the correction of mistakes or what Charlie Munger called “thumb-sucking.” Problems, he would tell me, cannot be wished away. They require action, however uncomfortable that may be.”

On Big Decisions - “…our experience is that a single winning decision can make a breathtaking difference over time. (Think GEICO as a business decision, Ajit Jain as a managerial decision and my luck in finding Charlie Munger as a one-of-a-kind partner, personal advisor and steadfast friend.) Mistakes fade away; winners can forever blossom.”

On Mistakes - “During the 2019-23 period, I have used the words “mistake” or “error” 16 times in my letters to you. Many other huge companies have never used either word over that span. Amazon, I should acknowledge, made some brutally candid observations in its 2021 letter. Elsewhere, it has generally been happy talk and pictures. I have also been a director of large public companies at which “mistake” or “wrong” were forbidden words at board meetings or analyst calls. That taboo, implying managerial perfection, always made me nervous (though, at times, there could be legal issues that make limited discussion advisable. We live in a very litigious society.)”

Michael Mauboussin - Probabilities and Payoffs: The Practicalities and Psychology of Expected Value

Mauboussin publishes some of my favorite investment research and gets into sports/decision-making from time to time. This piece is about probabilities applied to investing, but here are some takeaways (note: everything below is verbatim from the paper):

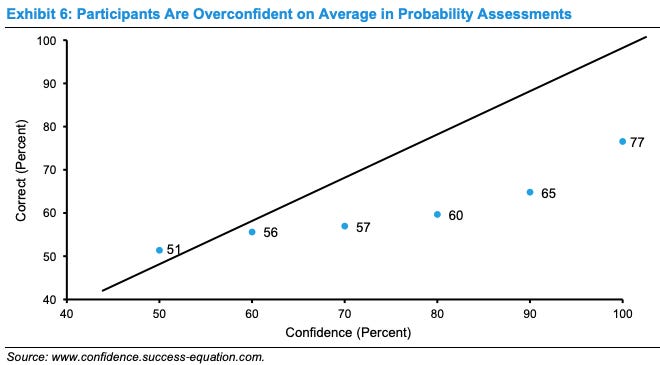

Feedback and calibration. In decision-making, calibration measures the degree to which someone’s subjective assessment, a measure of confidence, aligns with how often they are correct. Exhibit 6 shows a classic example: thousands of participants answered 50 true-false questions and indicated their confidence in their response for each. The exhibit shows that the confidence of the participants exceeds their correctness in the aggregate. For example, when they are 100 percent sure they know the answer, participants are correct only 77 percent of the time. Psychologists have replicated this finding many times.

Words to probability. People assign different probabilities to the same word or phrase. This introduces the potential for miscommunication. Exhibit 5 shows some of the results of a survey of more than 3,000 respondents who were presented with words or phrases, in random order, and asked to assign probabilities to each.

Control and reversibility. Because payoffs reflect future states of the world, it is important to understand when the payoffs are expected to happen (time horizon), whether the decision-maker can alter the payoffs (control), and if the investment can be exited at an acceptable cost (reversibility).

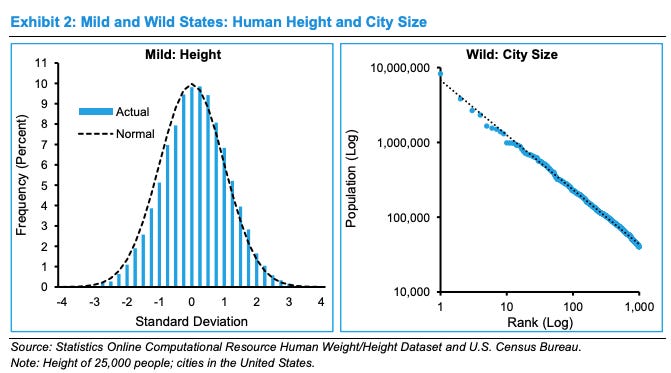

Consider the shape of the distribution of payoffs. Benoit Mandelbrot, a renowned mathematician, used the terms “mild” and “wild” to distinguish between the ranges of future states. Mild states can generally be captured with a normal, bell-shaped distribution. The distribution of the height of people, for instance, is mild, with the ratio between the tallest and shortest humans on record being five-to-one (left panel of exhibit 2). Statistical concepts such as mean (average) and standard deviation are useful in expressing mild states. Wild states are often power laws, where few very large outcomes have a disproportionate impact on the distribution.